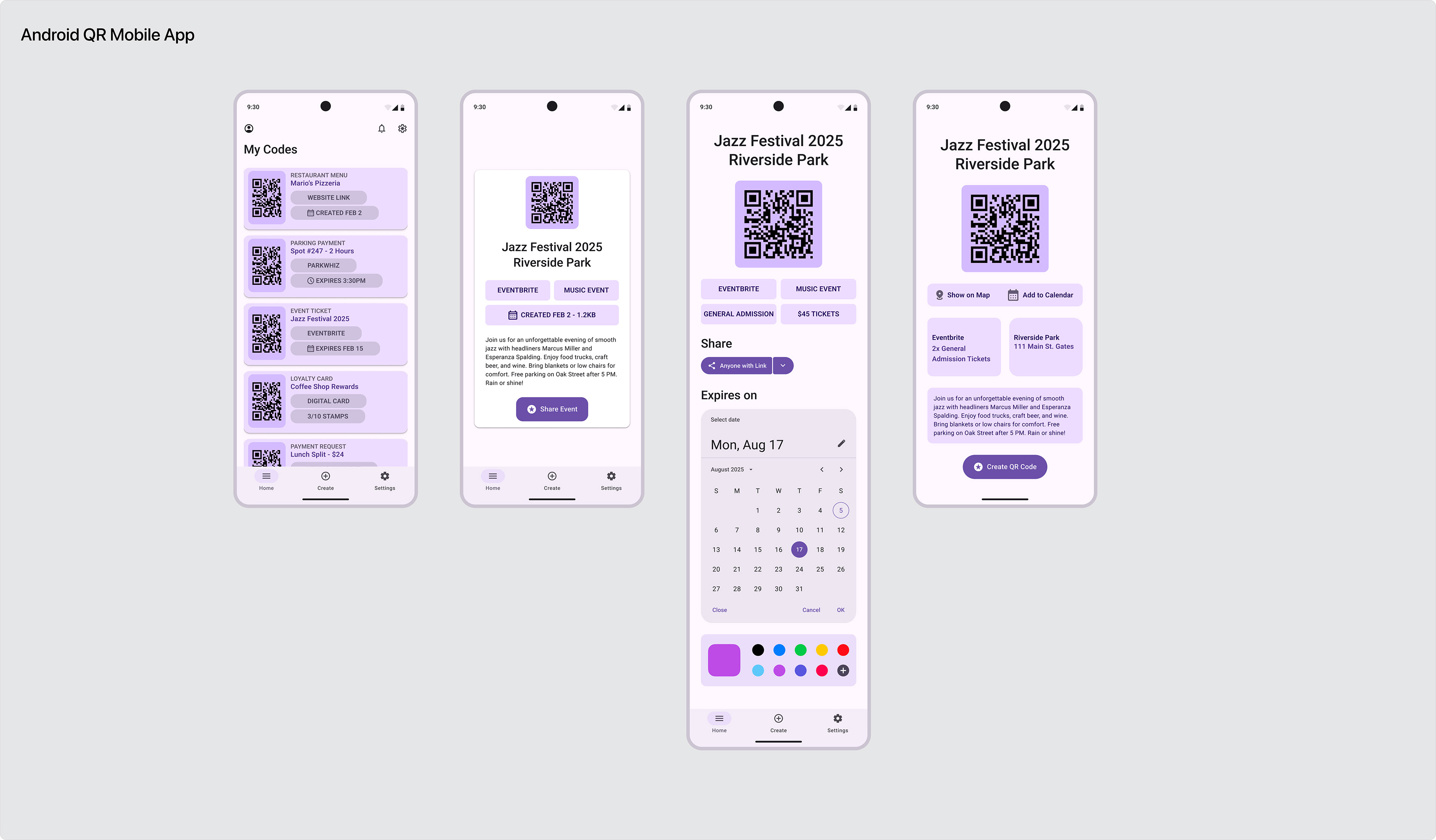

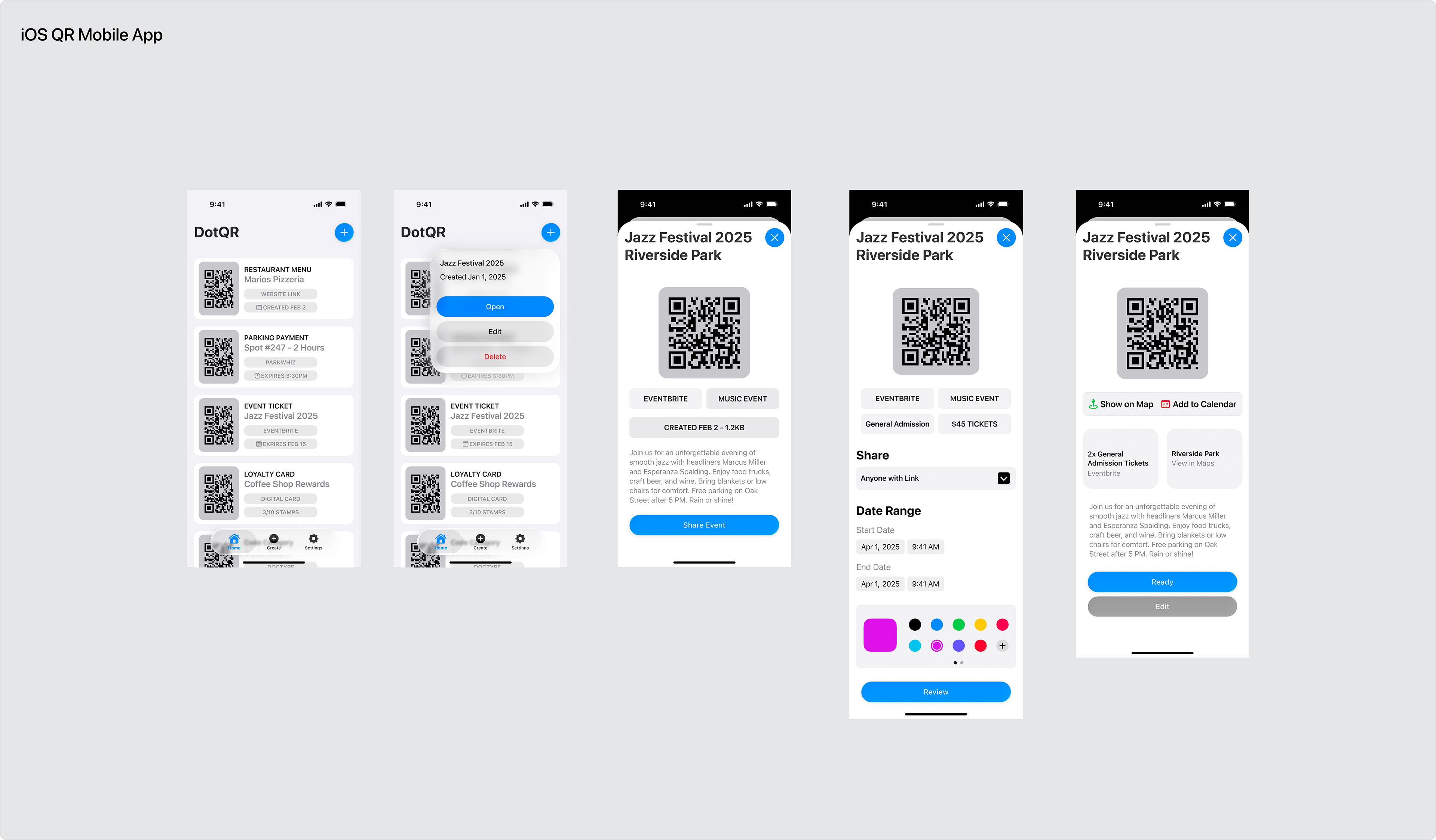

DotQR (.qr)

Year: 2026

Tools: Figma, Whimsical, Rive, Notion, Are.na

Skills: Information Architecture, User Research, Journey Mapping, Wireframing, Prototyping, Design Systems, Accessibility, Responsive Design

Year: 2026

Tools: Figma, Whimsical, Rive, Notion, Are.na

Skills: Information Architecture, User Research, Journey Mapping, Wireframing, Prototyping, Design Systems, Accessibility, Responsive Design

QR codes are now ubiquitous. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated their transition from being seen as “that strange square barcode thing” to becoming a part of our everyday infrastructure. Used for restaurant menus, event tickets, parking payments, vaccine passes, package tracking, and building access. The market for QR codes is projected to reach $35 billion by 2030 (Link), reflecting significant growth and innovation potential, which should inspire technology professionals and business owners to explore new developments. However, one key observation is that although QR codes have evolved into a primary interface, the actual user experience associated with them has not advanced at all.

When you scan a QR code on an iPhone, the camera recognizes it, and you receive a notification. By tapping on this notification, you are instantly directed to the URL embedded within the code. There’s no preview or verification step to confirm what you are about to open. This interaction model assumes that QR codes are trustworthy and that instant access is always desirable. While this made sense when QR codes were rare and primarily used for marketing campaigns, it is far less justifiable now that they are widely used for payments, identity verification, and access control.

The absence of a preview is not merely a minor user experience issue; it also poses a security vulnerability. Malicious QR codes can be placed over legitimate ones, and phishing attacks can disguise themselves as restaurant menus or parking payment systems. Even in non-malicious scenarios, there is no way to know whether the code you are scanning is expired or if it will lead you to a mobile-friendly page or prompt a file download. Essentially, you are scanning without visibility.

What If We Added a Preview?

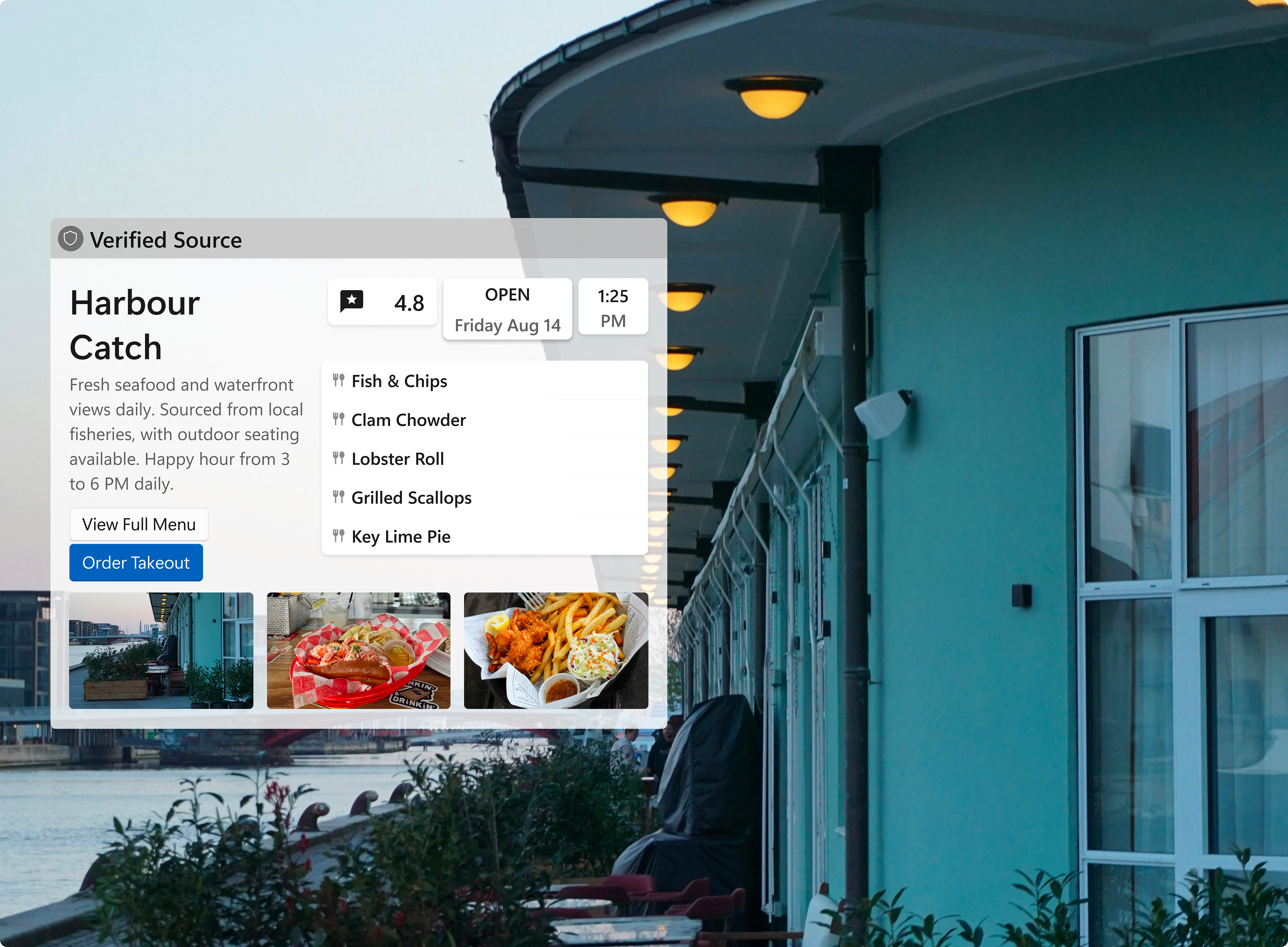

I began with a simple question: What should occur in the moment between detection and action to support user choices, especially regarding safety and trust? What if, instead of immediately opening a link, your camera displayed a preview overlay that provided just enough information to help you make an informed decision?

This preview would appear as a floating card as soon as your camera detects a QR code, showing you three essential pieces of information: the type of content (e.g., website, contact card, WiFi network, event ticket), the destination (the actual URL or relevant details), and whether the source is verified. Providing this information helps build trust and transparency, making users feel more comfortable before opening links.

The key insight is that preview content should be contextual, not generic, to ensure relevance across various user scenarios. A preview overlay for every QR code shouldn’t look the same. What you need to know before scanning a restaurant menu is entirely different from what you need to know before scanning a shipping label. Tailoring previews to the content type helps users feel understood and supported in their specific context.

Context-Specific Previews

Restaurant Menu

A diner scans a QR code at a restaurant. The preview displays the restaurant’s name, cuisine type, and hours, then loads the full menu. This feature helps eliminate confusion in areas where multiple establishments operate close together.Event Poster

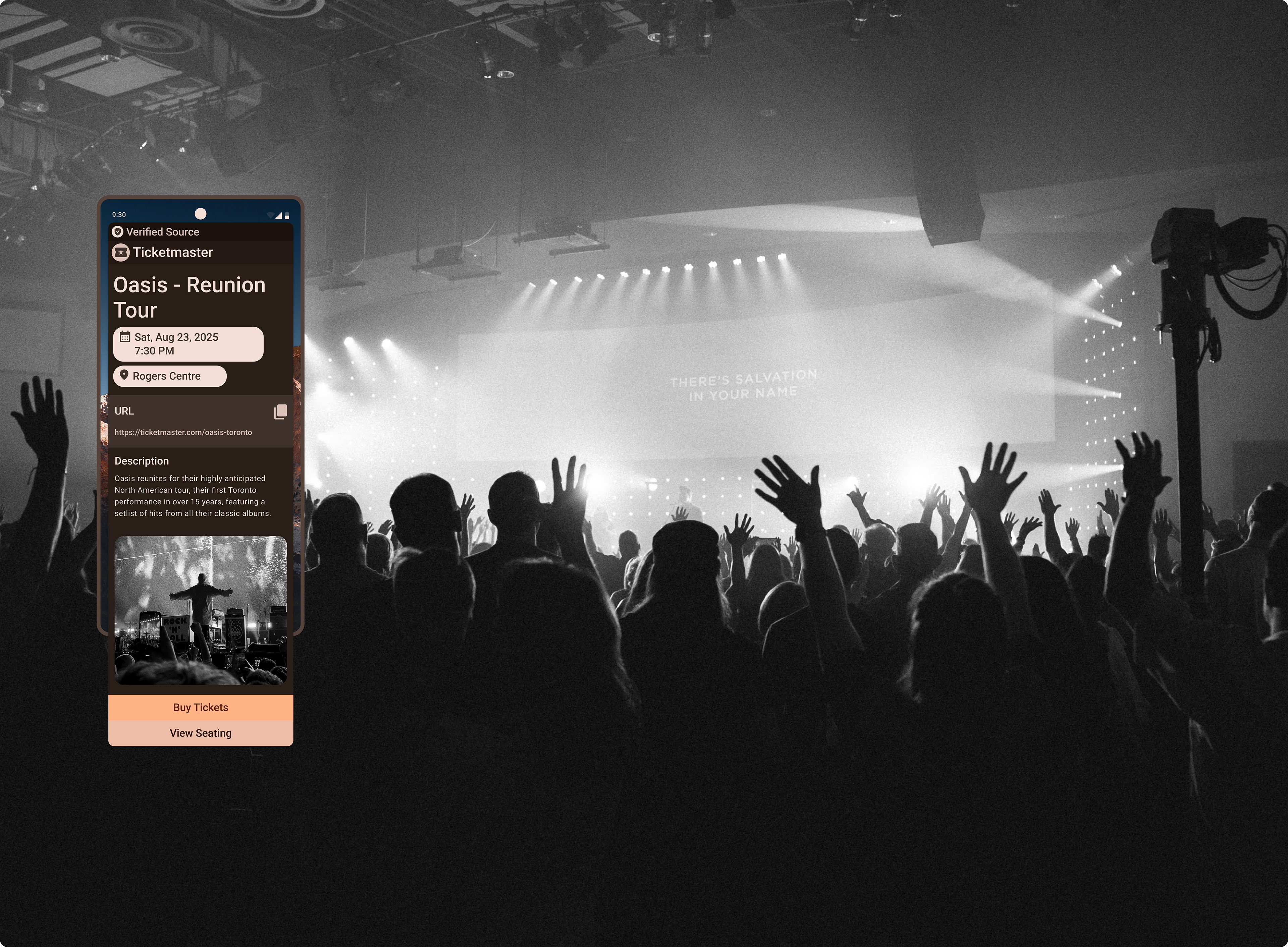

A concert-goer scans a poster downtown. The preview immediately shows the event name, date, venue, and ticket price range, allowing them to decide whether to proceed to ticketing without leaving their current app.

Shipping Label

A warehouse worker scans a BOL code. Progressive disclosure first shows the tracking status, with the option to expand for full manifest details, including dimensions, contacts, and itemized contents. This approach provides precisely the information needed without unnecessary navigation.

Treating QR Codes as Files, Not Images

Currently, when you scan a restaurant menu QR code, you’re likely just accessing a URL that links to a PDF hosted on their website. The QR code itself is a static image, either a PNG or SVG that encodes a simple string of text. There’s no metadata, no structure, and no ability to update it after creation.

As I continued designing contextual previews, I realized that embedding structured data in QR codes can empower developers and stakeholders to create more dynamic, valuable solutions. A restaurant menu QR code should include information about the restaurant itself, not just a link. An event ticket should carry structured event data, and a shipping label should contain package details.

This shift in perspective led me to view QR codes less as images and more as documents.

When PDFs were introduced, they addressed a specific need: a file format that would display consistently across all devices, could package text and images together, and was easily shareable and printable. PDFs became an industry standard because they filled a real infrastructural gap.

QR codes serve a similar need in reverse: they act as a physical interface to digital content. As QR codes become more widespread and essential, we need better infrastructure to support them. We require a standardized method for creating, editing, managing, and encoding structured data within them, enabling industry leaders to define the future of this technology.

This is when I began considering a new file format, which I propose to call .qr. It wouldn’t merely be a PNG encoding a URL; it would be a file that includes the encoded data along with metadata: when it was created, who created it, what type of content it links to, when it expires, version history if it has been edited, and security signatures if it originates from a verified source.